Murano glass plates, functional objects that give beauty

When dishes are prepared with art in the kitchen and need to be presented with care, Murano glass becomes a fundamental material. This is what

The old and the new, adherence to traditional values and a desire to innovate, are currently engaged in an endless discussion in the Murano glassmaking community.

The fact that this conversation is taking place between artists who only exist in the present and glassmakers who operate in a setting reminiscent of a medieval workshop is what makes it so rich.

It is a fact that some of the glassmaking companies that are most receptive to modern inventions are also constantly dedicated to maintaining the high level of the most sophisticated processes, that some gaffers who work in these factories are committed to maintaining the highest degree of grew up honing their ancient manual talents and have become the leaders of the most current glassware fashions.

Notable figures from the fields of contemporary design and art are also eager to use the island’s furnaces. All of this demonstrates that this discourse is not only feasible but also yields worthwhile outcomes.

The coexistence of two diametrically opposed cultural viewpoints is not always simple. It is difficult to reconcile the continued use of such an antiquated technological legacy, inextricably tied to typologies and stylistic elements of the past, in the recollections of people who work with them directly, with the most daring movements in art and design.

Moreover, the models that have been developed over many years serve as a constant and necessary benchmark. The debate might devolve into schizophrenia, and the need to balance the present with the future could cause the glassmakers, designers, and even the manufacturers to have an identity crisis as they observe the market voicing conflicting demands.

Overall, though, Murano is an exceptional example of how the past can be preserved while being open to the future, much more so than in other old crafts. It has been able to confront the challenge of modern art with both sensitivity and wisdom.

Beginning with its earliest beginnings, the whole history of contemporary Venetian glassmaking has been marked by a persistent, though occasionally unintentional, desire to comprehend and interpret the most cutting-edge advances occurring outside of its borders without compromising its past.

Murano’s glassmakers and designers have frequently felt the need to revisit the past during difficult times, such as shortly following World War II and subsequently, in order to discover a unique and in some way “local” key for understanding modern society.

This has often been quite effective.

Foreign glassmakers abandoned their traditional forms, namely 19th century revivals, as early as the 1880s in France, partially due to the impact of japonisme and exactly when painters were creating a new sort of art, Art Nouveau.

This style was centered on mimicking nature as a direct inspiration source, as stylized so exquisitely in the Far East, as opposed to copying earlier works of art. Nonetheless, around the same time period, Venetian glassmakers continued to operate in accordance with 19th century modules because they were committed to their heritage and were excited about reviving old methods and the ensuing financial success.

In order to create a powerful incentive for the nascent tourism sector, Venice itself was not particularly receptive to the new creative movements. Even the inaugural Biennale d’Arte exhibition in 1895 failed to inspire renewal since it had a very conventional posture in the beginning of its activity. The Murano Council debuted a sizable display of modern Murano glass in the Museo Vetrario on the occasion of the first Biennale, but although having a number of pieces of exceptional dexterity, it lacked a sense of the modern.

To build a new artistic language, it took around twenty years, interspersed with modest inventive suggestions, mostly from the Toso and Barovier glassworks. But, the movement of the Ca’ Pesaro artists in Venice gave the process later impetus. Around the Bevilacqua La Masa Foundation, which was then situated in Ca’ Pesaro, a group of painters became active who were all dissidents against official art while adhering to various trends.

These painters kept their studios in this structure and held displays of their avant-garde works that had a striking visual effect.

Also, there was ornamental art on display, some of it created by the artists themselves and some by skilled craftsmen. Several of them, like Vittorio Zecchin, Teodoro Wolf-Ferrari, Giuseppe Barovier, and Vittorio Toso Borella, were glass designers and craftsmen. The first pieces in the Art Nouveau and Secessionist styles were produced in this manner.

The mosaic glass (murrina) method, first employed in Roman times and resurrected in the 1870s, was chief among the highly sophisticated processes used to manufacture them, although these works belonged to discrete groups of one-off productions.

They were shown at the Biennale exhibitions in 1912 and 1914 alongside works by German artist Hans Stoltemberg Lerche, who worked in Rome, and Venetian wrought-iron artist Umberto Bellotto, whose creations combined iron and glass. The rest of the production, however, continued to follow 19th century trends.

A fundamental revival did not occur until after World War I, when functionalism and the contemporary style, which sought exquisite but sensible interior décor, gained momentum.

While Murano appeared to be impossible to advance into modernity, a new business founded in 1921 by Giacomo Cappellin and Paolo Venini paved the way. They requested the local painter and creative director Viltorio Zecchin to produce a collection of real Murano masterpieces that also followed the latest fashions. The simplest ancient blown-glass objects depicted in the works of the greatest painters of the 16th century served as Zecchin’s source of inspiration. These works suggested an authentic Murano style with the lightness and elegant rounded shapes that the glassblowing process itself prompted, thin walls, and complete transparency.

A few vintage models, like the Veronese vase, were faithfully recreated, but the designer also unveiled a whole catalog full of unique forms, including chandeliers, table settings, and vases, that had the same qualities as the new, opulent interior design. The product was an instant hit both domestically and internationally, and other businesses started to imitate it. The formal repertoire from the 16th century has become standard for modern glassmakers as a result of the experience of the 1920s.

As a result of the presence on Murano of the very competent engraver Franz Pelzel, wheel engraving rose to popularity. He received his education in Bohemia and was hired by the S.A.L.I.R. workshop, where he was to instruct a sizable group of young engravers.

The Tosos, Ferro-Tosos, and Baroviers continued to make their brightly colored murrina glass throughout the same time frame. With the exception of a brief period in the late 1920s and early 1930s, when enthusiasm waned and the major creators of the Nocevento design were Ercole Barovier, Napoleone Martinuzzi, Flavio Poli, and Carlo Scarpa, this vibrant decorative approach was unmistakably contemporary. The so-called “Novecento” style—literally, the twentieth century, though it only applied to the 1930s—led to a reversal of fashion trends as well as to a substantial advance in technology.

Due to a movement that began in Italy in the early 1920s and was connected to the Realism revolutions in other European nations, the new style was intimately associated with the Novecento art and sculpture of the same era.

It explored the fundamental principles of forms and suggested a clear fluidity of shapes while laced with ancient memories.

It introduced strong structures and at times stark classicism to architecture. The lightness and ornamental beauty of Art Déco began to be rejected in the minor arts, especially glassmaking, in favor of solid, traditional or archaic-looking designs that were inappropriate for translucent thin-walled glass.

Opaque or pulegoso glass, which has a lot of irregular bubbles, was chosen to ensure that vases, which again had to be bulkier, were more solid. Later, thick transparent glass with internal layers of different colors (sommerso or “cased glass”), bubbles, or gold or silver leaf elements and other impacts obtained using varied different techniques were chosen. While working with pulegoso glass was unique, working with thick sommerso glass or inclusions was completely new to Murano, so the glassmakers had to pick up these specialized abilities from scratch. The emergence of a new glassmaking industry—glass sculpture that was first blown and then solidified—was another intriguing development.

Glassmakers have never attempted to create substantial sculptures by physically modeling the hot glass outside of Murano. Without any prior knowledge, they had to learn how to model the raw material and produce vegetable and animal shapes.

As the first apprentices of those pioneers and subsequently those who learned from the apprentices are now well-known masters of glass sculpture, even abstract sculpting, it was an experience that opened up new potential for Murano glass. Only one of those original explorers is still in business. He is Alfredo Barbini, a pivotal figure in Venetian glassmaking throughout the 20th century, who is 91 years old.

The first sectional module-based roof and wall-mounted accessories were created in those same years. While it is still present in the Murano repertory, this invention was to flourish quickly after the war until the ’70s, and then come to a rest owing to market saturation.

Techniques of a completely different sort, including murrhine and filigree, which had already been a part of the local history, were obviously disregarded during this time of fondness for sculpted glass.

Yet the brilliant Carlo Scarpa had the foresight to go against the grain and employ these methods early on.

The creation of sculpted and sommerso (cased) glass was concurrent with a return to traditional methods and thin, daringly contemporary blown glass in the 1950s as a response to the Novecento style. The 20th century’s most vibrant and successful decade was that one.

Entrepreneurs occupied themselves with updating their manufacturing, many of them enhanced the quality of their products, and new, sometimes even sizable factories were created, encouraging the gaffers to take on expensive and top-level work.

With the assistance of the masters, the presence of developers in the glassworks became routine, and even well-known figures from the art world traveled to Murano to test their proficiency with glass and the regional techniques.

Each business made an attempt to create its own aesthetic, focusing its technical and creative efforts on specific goals.

Filigree was used in novel ways that had nothing in common with the prehistoric models, yielding unexpected outcomes. Very polished works and items with a big effect exalted the decorative possibilities of blown and non-blown murrina glass.

A particularly prosperous time was enjoyed by engraving and the Carlo Scarpa-developed battuto method, which included coating the entire glass surface with minute, nearby engraved lines or circles.

The glassmakers who had been schooled in the Novecento style produced sculpture in two parallel and opposing directions.

There was conceptual sculpture, or sculpture that in any case was the consequence of an incredibly sophisticated formal synthesis, on the one hand, and realistic or hideous sculpture, rich in detail and dexterity, on the other.

By utilizing the “Fucina degli Angeli,” Murano’s expert glassmakers were able to produce glass creations inspired by well-known artists like Chagall, Picasso, and Fontana.

The works, which were mostly sculptures, started a tradition that has persisted ever since. Even when the pieces were created by the glassmakers themselves, they demonstrated that they had caught the zeitgeist and had the ability to translate the avant-garde artists’ concepts into the material of glass.

The glassmaking art of the 1950s was characterized by daring and sometimes exceedingly sophisticated polychromy, and modern designers and glassmakers continue to look to those pieces as a source of inspiration, a model of innovation, and the audacious.

As minimalism, which made extensive use of polymeric products and industrial processes in the creation of furniture and decorative things, won in the 1960s and 1970s, the previous excitement faded away, attacking anything that had to do with heritage.

Blacks, whites, clear crystal, and monochromy often predominated since the idea of embellishment was condemned as blasphemous. The factories who lacked modern designers were caught off guard by this reversal in market demand patterns, but the volatility of the social climate soon made matters worse. So much so that, in the early ’80s, a number of companies shut down and others changed hands, sometimes under painful conditions.

Molds became widely used, with a preference for “non-rotating” moulds (asymmetrical moulds inside of which the product was not converted while the blowing process took place), in their attempts to make glass goods that conceded nothing to decoration, with a limited and “poor” look, aesthetic similar to industrial products, or primitive and seemingly improvised.

Several really intriguing pieces were more in line with modern sculpture and painting than with earlier Murano-produced pieces. At this time, the market for architectural lighting equipment experienced fast growth. Grandiose cascades of segmental pieces, compositions of modules intended to cover entire walls or the ceiling, and the “hook” created by the Vistosi glassworks represented novel ideas. This component had the appearance of a modelling rope that could sustain itself and be bent into the shape of a glass curtain. Chandeliers were viewed as being excessively big and out of date, therefore other glassworks also provided conventional table and hanging lights. Glass tiles, screens, and doors cast on plates in a variety of colors, primarily opalescent, were widely produced.

Studying and collecting historical glass objects from the Art Nouveau era and up until the 1950s became popular in the nineteen-eighties, and interest in the standard technologies and color was rekindled. As a result, the glassmakers resumed producing glass in a way that was connected to Murano’s history. Traditional ornamental polychrome glass methods have been revived, but they have been reinterpreted in light of contemporary trends in both glassmaking and art.

The craft of glassmaking regained popularity after appearing to have lost steam for a number of decades, and as a result, innovative endeavors quickly restarted, inspired by the exploration of artifacts from the 1920s through the 1950s.

This feature of interior décor, which began as exact replicas of several chandelier models created in the 1940s and 1950s, has successfully reemerged in contemporary and occasionally quite opulent forms. Artists and designers arrived to Murano once more in the 1950s, eager to express their work in glass.

End of the 20th century and the first years of the 21st century modern glassmaking are moving in two separate paths. The one is more modern, while the other is based on traditional production, which has gotten a boost and the benefit of passing down methods that may otherwise be lost.

While some glass companies hire extremely contemporary designers on a temporary basis, others have their own artistic managers who have long worked in the glass industry.

The great master glassmakers who have created their own language through collaboration and experience with other artists and designers, as well as independent designers who have introduced fresh concepts to Venetian glassmaking, are the ones who set the current trends. They work for themselves and create unique designs based on their own sensibilities. Although they don’t actually model the glass, they collaborate closely with the masters and impose new aesthetics.

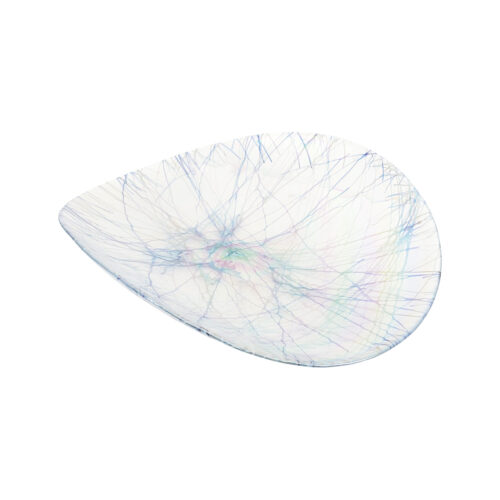

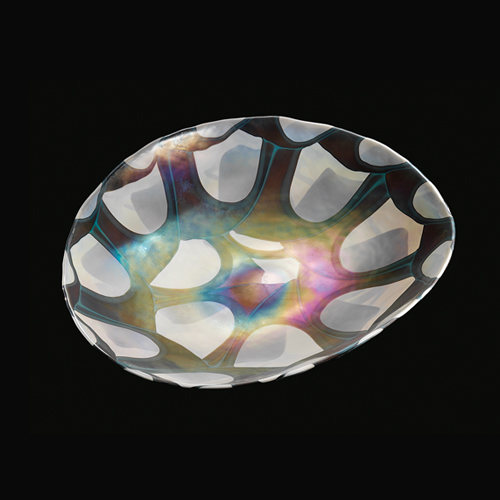

Here begins the work of the Ferro family, who begins to experiment with new shapes and new colors, inventing shapes such as the shell and the foil, or experiments with different chemical compositions creating the colors that distinguish Yalos Murano products.

There is no preferred technique since each individual uses the medium that best expresses his or her individual artistic vision within the broad technological repertory of Murano. Some people favor sculpted and solid glass, some find blown glass fascinating, and yet others adore murrhine glass for its colorful richness. In any event, the vase is the most popular subject, not because it serves a practical purpose but rather because it has served as a model for harmonious shapes and a canvas for creating surfaces with pictorial or graphic value, transparencies, or, on the opposite extreme of the spectrum, effects related to the glittering preciousness of opaque glass throughout history.

The endless diversity of pieces created by the Murano glassmaking facilities are evidence of the material’s limitless possibilities. However there is still a lot that needs to be learned and created.

When dishes are prepared with art in the kitchen and need to be presented with care, Murano glass becomes a fundamental material. This is what

The old and the new, adherence to traditional values and a desire to innovate, are currently engaged in an endless discussion in the Murano glassmaking

Have you ever wondered how just one small kitchen accessory could further expose more of who you are? It’s now time to unravel a piece

Ever enter a room and find that one brilliant object that just mesmerizes you? Well, that is the magic that Murano Glass vases carry. These

Signup our newsletter to get update information, news & insight